Author and artist Hannah Hudson-Lee is inspired by nature. She uses her artistic talents to create detailed illustrations, including those we share with you as Christmas cards.

The phrase, “The Wisdom of Solomon,” does not immediately make me think of the Old Testament king. It makes me think about my middle school art teacher Miss Solomon, who, like her namesake, was also incredibly wise.

My favourite art project Miss Solomon set us involved studying the beautiful artwork in botany and ornithology books from 1660-1960 to produce our own illustration. At the time, most new wildlife identification books were starting to use photographs, and Miss Soloman thought this was a crying shame. She explained to us that, whilst photographs are fantastic for capturing the action of wildlife and the context of the surrounding habitat, they are not as useful as an illustration when you want to identify a species.

First, catch your jackdaw…

Say you are an artist setting out to create an illustration of a jackdaw for an ornithology book. Your first step is to observe as many examples of the species as you can. Jackdaws in the wild, photographs of jackdaws, and even old preserved specimens in museums. You need to REALLY observe. Does that feather lie over or under that one? How many toes? Which way do the eyes point? As Miss Solomon said, “In art, it is more important to know how to observe, than it is to know how to draw.” (I told you she was wise). Then the artist uses all their research to draw a perfect example of an average jackdaw. This jackdaw does not exist in real life. It is a distilled essence of jackdaw or, if you are a fan of the philosophy of Plato, the Perfect Form of Jackdaw.

In a photograph, the individual jackdaw that has been captured might have an injury or an unusual genetic variation. For example, there is a jackdaw with a crossed bill that visits my Mother-in-law’s bird table. If you were trying to use a photograph of that jackdaw to identify another jackdaw, you might be forgiven for incorrectly assuming that all jackdaws have crossed bills. In contrast, a good scientific illustration removes these confusing variations. It can also highlight the key identifying features by posing the jackdaw in such a way that they are clearly visible. (It’s really hard to get a jackdaw to pose just-so for a photo. Though perhaps not completely impossible, jackdaws are pretty bright.)

Put another way, a photo of a jackdaw is like a Google Earth image. Capturing one moment in time. A scientific illustration of a jackdaw is the equivalent of Google Maps. Each have their uses, but frequently, the map is what you really need. The important information is much clearer.

Take a wild guess

I became absolutely fascinated by the examples of illustrations Miss Solomon showed us. Particularly Beatrix Potter’s Mycology drawings and the stunning ornithological illustrations of Arthur Singer. We were particularly charmed by the paintings by Tupia, a Ra’iatean who joined the Endeavor expedition in Tahiti. Tupia taught the crew and scientists aboard many things about navigation and the Pacific. He in turn tried his hand at learning painting in the European style. As people learning ourselves, it was great to see the work of another student, albeit one from over 200 years ago. The human figures he drew may have been a little awkward at first, but his lobster was spot on!

Best of all were the examples Miss Solomon showed us where the scientific illustrators didn’t have enough information to go on, and as a result got things hilariously wrong. Back in the 1700s an illustrator might never have seen the creature in question in the wild. They often worked from a single stuffed specimen and some field sketches made by scientists on their far-flung expeditions. Unfortunately, sometimes the taxidermist didn’t know what the animal looked like when it was alive either. They were essentially filling a feathery or furry skin bag and had to guess the correct shape. Perhaps the cutest example is a painting of a Kangaroo by George Stubbs. The artist’s model was a stuffed specimen bought back from James Cook’s controversial first Pacific voyage. It looks a lot more like that giant mouse that chases you in your nightmares than a kangaroo.

Getting there

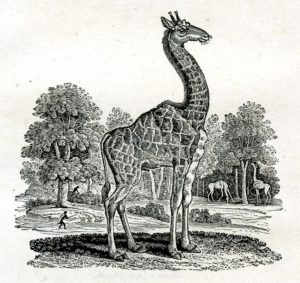

Cameleopard, Thomas Bewick ©Trustees of the British Museum

I am also very fond of the giraffe with a hump from Thomas Bewick’s A General History of Quadrupeds (1790). The hump happened because the taxidermist knew that the scientific name for a giraffe was “Cameleopardus” or camel-leopard, so he gave the specimen a hump! This was then replicated in the drawing.

Arctic Skua ©H. Hudson-Lee

When the time came to produce our own work, I chose the Arctic Skua to draw. Not the most colourful of birds, but they have intricate patterns in their plumage, and I took obsessive pleasure in detailing every feather. Miss Solomon had planted a seed in my fertile young mind, and I was very pleased with my end result.

I kept drawing, and by the time I was an undergraduate at university, friends were asking me to help illustrate their theses. I drew a lot of fossils and what felt like a metric load of squirrels.

Art for art’s sake, to create a fantasy, to beautify or to make a statement, is a joy to be sure. But art is also a powerful and vital tool, in the world of science. We use it to visualise data, to record observations, to teach and to explain. If you have a yen to study art, and someone trots out the old chestnut, “It’s not very useful for a “proper” career”, feel free to point out that, without the work of artists, they wouldn’t know what the solar system looks like, they wouldn’t be able to picture the structure of an atom in their mind’s eye, and they wouldn’t have been able to learn about the structure of a human heart at school without having to do a bit of extracurricular grave robbing and some messy dissections. As wise Miss Solomon helped us understand, art is very useful indeed.

A slightly warped look at wildlife

Today, my wildlife inspired work has taken a lighter turn, with the aim of using art and humour to help people engage with the natural world.

One of my projects “Second Bestiary” creates new creatures by changing one letter of their name. Examples have included, the Hengehog, the Wraptor, the Guffer Fish, the Ginnow (& tonic) and the Yarn Owl (a creature of the knit). My home in South Yorkshire is surrounded by fantastic wild spaces managed by Sheffield and Rotherham Wildlife Trust. I frequently go to the reserves at Kilnhurst Ings, Greno Woods and Centenary Riverside when I need to observe the natural world for research or ideas. Inspiration is never more than a walk in in the wild away, and I truly treasure that privilege. This is why it was an honour and a pleasure to create the Christmas cards for 2020 and 2021, and to be currently working on a design to thank you for supporting the Trust through 2022 and beyond.

Hannah also creates weird beings and wonderful beasts of her own – visit idolscribblings.blog to discover more of her work.

All British Museum images are available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)